History of the Boca Grande Health Clinic

Written by Lynne Hendricks

Published by the Boca Beacon – February, 1997

Foreword

1997 marked the 50th year that the Boca Grande Health Clinic Inc. has been providing medical care to the year-round residents, vacation homeowners, employees and visitors to our beautiful island paradise. Today most of these groups regard the existence of a good, local health care facility as a necessity to be able to live and work on a relatively remote barrier island.

However, the 50-year transition from an island with no doctor to an island with a modern, well-staffed clinic has not been easy. It was only accomplished through the exceptional foresight and leadership of certain residents together with very strong community support.

The current Board of Directors of the Clinic decided that it would be appropriate on the 50th anniversary of the clinic to publish a series of articles to chronicle some of the clinic’s more interesting developments over this period. While we were contemplating how to proceed with this formidable history project the Boca Beacon offered to retain Lynne Hendricks to research and write the clinic story. We are extremely grateful to the Boca Beacon and were so pleased with their efforts that we commissioned this publication of their work.

As readers of this book will note, successive generations of island residents have pulled together to make the Boca Grande Health Clinic so successful during the past 50 years. I am very confident that the same kind of community support will be available to the clinic for the next 50 years.

W.J. Carroll, President

Seaboard Railroad’s daily run to Gasparilla Island was an integral part of life for island residents. It brought needed supplies from the mainland, as well as visitors from the north, whom each day islanders turned out to the station to meet and greet. In the early days of the clinic, a doctor came from Arcadia, treated patients right in the Depot, then left by the same train three hours later. Photo was taken in downtown Boca Grande in about 1912. Photo courtesy of Jeff Gaines Jr.

There are few who remember what it was like to live on this barrier island under the most primitive of medical conditions, when coming down with the flu warranted the quarantine of one’s home, and when patients in need of immediate medical attention were transported to the mainland via a pull car over the railroad trestle.

Those who do remember, along with a number of letters and documents from the Boca Grande Health Clinic archives, tell the story of the clinic’s birth, and of the “pioneers” who did well to get sick on a Tuesday when the mainland doctor made his weekly 3-hour visit. More than that, they tell the story of a group of dedicated and compassionate people and a small town determined to take care of its own.

Naturally, one cannot speak of care, determination, and the clinic without mentioning the name of a very special woman who once wintered here. Most of us, at some time or another, have heard stories of her. For as many people whose lives she touched there is a story, and she touched many lives. Her name greets all those who pass through the clinic doors today, and it was she, Louise Du Pont Crowninshield, who took it upon herself to bring medical services to Boca Grande at whatever struggle or cost.

But a barn isn’t raised with the work of one, and although Louise’s guidance and vision carried the clinic through difficult beginnings, it was the community that built its foundation. It was the community that raised the clinic and carried it on their shoulders following the death of Mrs. Crowninshield, and it was the community that came together in times of need, contributing whatever they could afford to keep it going. Similarly, it will be the community that sees the clinic through the challenges that lay ahead. With luck, we will meet those challenges as the earliest organizers met theirs, and the next fifty years will be as rich in story as the last.

The Beginnings….

Although the official records show that the clinic first opened its doors on March 15,1947, the day its charter was granted, handwritten notes discovered in old clinic files suggest it opened much earlier, ” … in 1938 by Louise Du Pont Crowninshield for the purpose of treating so called social diseases on the island.” There is only the one reference made to this early date, but those who remember agree that Mrs. Crowninshield probably did bring in a doctor to treat such diseases, since she was very concerned with the state of affairs, as it were, at the south end of the island in the 1940s.

As one islander remembers it, the port at the south end was bustling at the time, and there were sailors coming from all around the world docking up daily. With them they brought cultural diversity to the island, but left behind sickness of one kind or another acquired on the long journey to Boca Grande. According to island daughter Barbara Chatham, whose father, Sam Whidden, was one of the first to settle on Gasparilla Island, the majority of them suffered from the same thing and their plight was well known.

“They all went into the clinic and came out with the same little bottles,” she said.

Although most of the sicknesses were caught and treated by Seaboard Railroad’s quarantine doctor, some were more difficult to detect, and it was probably Mrs. Crowninshield that paid for the treatment of such sicknesses.

But special circumstances excluded, there is nothing in clinic files to suggest the regularity of visits from a mainland doctor prior to 1947. So what was a sick person to do in those days? Well, they made do. There weren’t many situations that couldn’t be handled by “Doc” Kennedy, the pharmacist over at Fugate’s. He could prescribe medication to ease symptoms of the common cold, the occasional cough or sore throat, and a variety of other ailments. And during the winter season a doctor was brought in by the Gasparilla Inn for its guests, and he was available to those who truly needed treatment. The quarantine doctor brought in by the railroad sometimes saw patients as well, but if the situation were serious islanders traveled to Tampa, according to Barbara’s sister, Isabelle Whidden. That was the site of the nearest hospital. In the case of emergency, a patient was boarded onto a special flat-bed rail car for transport across the railroad trestle. “The Bull”, as lifetime resident Darrell Polk remembers it, was pulled across the railroad tracks by an electric rail car. It was set up to carry any wheel-based vehicle of reasonable weight, and carried patients to the other side of the tracks to Placida where they would then be taken to the nearest hospital. The Sheriff’s department kept a car on the other side for that very purpose, and according to Polk, so did some of the islanders. People were happy to oblige in the case of an emergency and it worked out quite well. There were many patients, however, who never made it to the other side. As quick as islanders could come together to help a friend in need, the response time wasn’t always quick enough.

“A lot of people would have babies at the bridge (trestle),” says Chatham.

As the island’s population continued to grow and improved communication brought more visitors from up north to winter at the Boca Grande Hotel and the Gasparilla Inn, it became increasingly evident that the existing medical situation was not good enough. Inconvenience aside, it was expensive to travel to and from the island in those days – $5 for a round-trip on the ferry ($8 for winter residents), and many people could not afford the expense. Boca Grande needed its own doctor, and the task of bringing one here fell on the shoulders of the community’s strongest.

Louise Du Pont Crowninshield first came to Boca Grande in 1917. She spent 40 winters of her life here and in that time, touched the lives of nearly everyone on the island. She was instrumental in the building of the island’s school (now the Community Center) and the Community House, and was the founder of the Boca Grande Health Clinic.

Louise DuPont Crowninshield led the charge as she led many others. Married to Francis “Frank” Boardman Crowninshield (of the Salem, Mass. Crowninshield family of shipmasters and merchants) she first came to Boca Grande in 1917. She was instrumental in the building of the island’s school (The Community Center) and Community House and brought the same dedication to the clinic effort. Her legacy is alive today through the tangible role those buildings play in our lives, but her real legacy of compassion and love is less tangible and grows more so as time passes and those who remember cease remembering. More than most can lay claim to, she built a bridge among people, and with love she tended its growth.

The kindnesses she showed to so many are too numerous to document in these pages and if listed, would do little to capture the spirit with which they were given or received. It’s difficult, after all, to measure a kindness – especially looking back at them fifty or sixty years later.

She gave Jonnie Thompson a dress once, but how can you measure the worth of such a gift. As Jonnie tells it, her husband, Pershing (one of the founding members of the clinic), was serving in World War II at the time, and she was manning the island’s telegraph station when word came over the wire that Pershing was missing in action. In fact, he had been taken prisoner of war and after six months time islanders came to believe he would not be coming back. They planted a tree in his memory. But at the close of the war when the allied army was laying waste to the concentration camps he was found alive and almost well, and words reached Boca Grande that their native son would be returning home.

Founding member of the Boca Grande Health Clinic Pershing Thompson served on the clinic board for 15 years, several as its vice president. Photo courtesy of Pershing and Jonnie Thompson

Mrs. Crowninshield was on her way north when she heard the news and sent young Jonnie a new dress from Lord and Taylor to wear to the station to greet him.

“And it was the right size,” says Jonnie.

That was over fifty years ago, yet when Jonnie recalls it today she is touched to the point of tears to remember the kindness. So perhaps the enduring memory of a kindness is measurement enough. Although Pershing himself suffered a stroke some ears back and lost a good portion of his long term memory, he says the memory of Mrs. Crowninshield has remained strong.

“I can remember things about her,” he said.

Pershing’s father named his son after General John J. Pershing of the Allied Armies in World War I, and when Mrs. Crowninshield learned of his namesake, she replied that she knew the General and proceeded to write him a letter telling him of the young boy in Boca Grande bearing his name. The General wrote back to her, replying how honored he was. Mrs. Crowninshield gave Pershing the letter and he has proudly kept it all these years.

She touched others lives in the same unique ways. At a time when racial divides were deep, Louise Crowninshield is remembered as being color blind, and the love shown to her by the black community is testimony to a love reciprocated.

As past Clinic President Frank Oliver recalled in a 1980 edition of “The Out Islander,” on the day Mrs. Crowninshield left the island for the last time, he was having drinks with a friend on Gilchrist Ave. when he heard the sound of a woman approaching on the sidewalk, “crying as if her heart would break.”

“I went out and saw the woman who had been Mrs. Crowninshield’s laundress for years. Her name I seem to remember was Annie May. I asked what the matter was and could I help. Shaking her head and with tears streaming down her face she said, ‘Mr. Oliver I bin to say goodbye to Mrs. Crowninshield. You know she bin good to your people and good to my people. I think when her time come there won’t be room on her crown for all the stars, they’ll have to put some on her robe.’”

If Annie May was right then Mrs. Crowninshield’s dedication to the health and well being of island residents through the clinic is well deserving of such a star. She knew how to get things done, and she surrounded herself with the kinds of people who could help her do it. To launch the clinic effort she assembled Wiley Crews, who supplied electricity to the island; Jeffrey Gaines, then Postmaster, Kiwanis Club President and owner of the service station in town; Pershing Thompson, who worked with Crews; Jerome Fugate, Sr., owner of Fugate’s soda shop/pharmacy/and sundry store; Hugh Rodney Sharp; and Johann Fust Library founder Roger Amory.

The Boca Grande Health Clinic began operations in 1947, working out of a small, rather primitive room on the top floor of the Railroad Depot where a doctor arriving on the train would treat patients weekly.

With the granting of the clinic’s charter in March of 1947, the group was ready to proceed – the first order of business being to secure a doctor. Through donations from a handful of island residents, they were able to hire a Dr. Kirkpatrick from Arcadia to come to Boca Grande one day a week. He would come on the train and leave with the train three hours later, and as Barbara and Isabelle remember, folks would do well to get sick on that day. Otherwise, it was still either the Inn doctor or the bull car for them. They both remember vividly one emergency that could not be handled by either.

It was mid-summer and the Inn doctor was no longer in residence when two little girls were playing upstairs in the depot building. Both wondered what it would be like to be shut inside the railroad’s big walk-in safe – if it truly did lock up air tight when you closed it. The soon discovered that it surely did, with one of the girls trapped inside. The community was in distress, and word was set to Dr. Kirkpatrick in Arcadia that he must come right away. Chatham remembers her father marching she and Isabelle down to the Depot to witness “what happens to little girls that run around and play instead of helping their Dad at the marina,” she said.

They had chairs lined up and everybody was praying,” says Chatham.

They had no combination and they were afraid she’d run out of air. She didn’t run out of air, and when Dr. Kirkpatrick arrived that evening, a safe specialist (a dubious distinction as Chatham thinks back) from Tampa was on his way to free her.

But it was situations such as this that prompted the clinic group to begin the difficult search for a year-round, on-island doctor. They began on February 19, 1948 at the first official meeting of the clinic board. The meeting was held at the Crowninshield’s studio on Gilchrist Ave., where the group would continue to assemble for some time.

They were each given their tasks at that meeting, the most important of which would be to spread the word that the position was open, and subsequently to raise the funds necessary to hire such a doctor. But by May of the same year, with little luck by word of mouth, the group decided to take out an advertisement in the Florida Medical Association’s Journal of Medicine. The advertisement read, “Doctor Wanted: General Practitioner for high class tourist town. Population, summer 400, winter 1,000. Have a clinic and could subsidize to a certain extent. Chance of a lifetime for the right man.”

Considerable time and effort was spent searching for the right man. Correspondence between Crowninshield and local leaders Wiley Crews and Jefferson Gaines prove the task was more difficult than anyone expected. But late that summer they received a letter from a Doctor J. J. Spencer of St. Augustine, Florida, and following a swift background check by Crowninshield, all were satisfied that they had found who they were looking for.

Like most of the responding doctors at that time, the 1917 graduate of the Medical College of Virginia had served in either one or both of the World Wars. Spencer served in World War I and graduated with a rating of Flight Surgeon from the Air Force School of Aviation Medicine. He served in WWII as well and returned to St. Augustine at the close of the war to start up a private practice. He came well recommended by a Dr. Walter Webb who wrote to Mrs. Crowninshield on September 22, 1948, “His father was a practicing physician in St. Augustine before my day here. Both his parents were of very good Charleston, So. Carolina families.”

As the clinic board had anticipated, the doctor would require a subsidy of $2,000 from the clinic as the practice would surely be too small to support him. To procure this subsidy, they launched the clinic’s first capital fund drive, asking residents to contribute at least $50 a year toward the fund. Mrs. Crowninshield defrayed the potential subsidy cost by offering one of her cottages, “The Courtyard Cottage” on First Street for the doctor to take up residence. The remaining funds they attempted to collect by contacting members of the beachfront and the managers of both hotels to ask what they would be willing to give.

Roger Amory, then the Clinic Board Secretary, was the first to respond, making a gift of full stock in the “San Marco Movie Theatre” on Park Ave. to benefit the clinic, valued at that time at just over $19,500. It was his intention that the principal and interest would be used solely for the purpose of increasing the medical services available to the people of Boca Grande. His gift, accepted on the day of his resignation from the Board, marked a significant turning point in clinic history. Through its involvement in the island’s only movie theatre and premier social attraction, the clinic drew more attention than ever before and folks began to think that this clinic idea just might work.

In 1948 clinic Secretary Roger Amory made a gift of the San Marco Theatre to benefit the health clinic. With his gift, the clinic was woven into the fabric of community life and was able to generate funds on a year-round basis. Photo courtesy of the Johann Fust Community Library

The Little Theatre, after all, was a big draw in those days. Prior to Mr. Amory’s purchase of the venue, it had been operating for some time under the management of J. E. Riley of the Boca Grande Land Co. As former Projectionist Darrell Polk remembers, the theatre had undergone extensive damage from a hurricane in 1947 and had been out of commission for a little while when Amory purchased it. A portion of the roof had been torn off and the equipment inside destroyed. It was Amory who restored it to its previous condition and made a gift of it shortly thereafter.

Polk worked under both owners. Although he was a young boy when the Land Co. was running the shows, his father had been a projectionist there, and when he was a junior in high school he was called upon to fill in for someone fallen ill. When he wasn’t filling in for Louis Lancel or Theo Hargis, Mr. Riley would employ him to hang up movie posters around the island. In exchange he was able to attend whatever movies he liked.

Later, when the clinic took it over, new Manager Wiley Crews asked that he take up the projection booth full time. For a long time he ran it alone and for some of the time with the help of Theo’s son, Don. He continued in that capacity even when the projection booth was transferred to the Community Center in the late 60s. If anyone could tell you something of the gay times had at the San Marco Theatre, it is Polk. After all, he enjoyed a unique perspective of the goings on there.

The San Marco Theatre was the center of social life on the island before it finally closed in 1967 and the movies were transferred to the Community Center. This photo was taken in 1970, several years before the building’s eventual restoration.

The ambience of the Theatre has changed considerably since the days of the San Marco. While dining today at the Theatre turned restaurant, it is difficult to imagine the perspective gleaned from a moviegoer entering the Theatre for the first time in 1947.

The building was more sparse to begin with. It had no real walls, for starters, and the roof was made of tin, which made for difficult acoustics during the rainy season.

“The back portion (nearest the entrance) was about twenty feet deep and was all wood floor,” remembers Polk.

That section was where the clinic installed its box seats. Each box seated approximately six people and was reserved for anyone willing to pay $25 for the evening – usually the winter residents.

“Once you got past that,” says Polk, “it was a regular beach shell floor with benches, and it was a little sloped.”

The benched seating was usually occupied by the locals, and during the time of segregation, there was a balcony above reserved for the island’s black population.

Despite the obvious separation of economy and race, folks remember the San Marco as being a place where everyone could take part and enjoyed being together. From the many stories told of her involvement with each member of the community, one assumes that Mrs. Crowninshield did much to instill the harmony that existed between the various walks of island life. For two nights a week the theatre played host to a full house, and according to Polk, Mrs. Crowninshield never missed a show.

“They used to accuse the manager of not starting the movie until she got there,” he said with a chuckle.

Polk remembers that on the two nights a week that the theatre was in operation, Fugate’s would stay open until movie’s end, when patrons would file down the street to take their places ’round the popular soda fountain.

Off to a Good Start

So it was, in 1948, that the clinic was woven into the fabric of community life. It was on its way. For the first time in its history, Boca Grande had its own on-site doctor. But with the doctor came the doctor’s shopping list – the equipment he would need to run a proper clinic. Most importantly, the clinic needed a proper facility.

Jerome Fugate had offered to rent part of his building out to the clinic, but such a move would necessitate a larger financial commitment on the part of the community – the hotel owners specifically. Although a permanent doctor was vital to the interests of both Sam Collier (Inn owner) and Joe Spadero (Boca Grande Hotel owner), by the following season, neither had yet responded to the clinic’s request for contributions.

Jerome Fugate was not only a founding member of the clinic, but was responsible for its very first expansion from the railroad depot to his building on 4th Street in 1949. Photo courtesy of Margaret and Delmar Fugate.

A subtly applied pressure was in order, and Mrs. Crowninshield managed the effort. On March 25, 1949 she wrote to Sam Collier, “The present situation over the station is not convenient. We have almost no running water and the stairs are too steep for anyone with heart disease or bad legs. In the past, the doctor was secured by Mr. Dunn (Inn Manager), with varying success – he only stayed while the Inn was open. This year the Inn has not had that expense, and the committee feels very strongly that the Gasparilla Inn should give a liberal subscription to this fund.”

There were few who could refuse a request from Crowninshield, and Sam Collier was no exception. His speedy reply was forthcoming, along with a commitment of $1,000 toward the clinic expansion.

On May 25, 1949, in a letter to Jefferson Gaines he wrote, “Since we would not have to keep a doctor at the Gasparilla Inn, we would be glad to pass on our saving to the clinic in the form of our contribution. It is understood, however, that this commitment applies only this one year, since we are all entering this more or less as an experiment.”

But more was needed. Fugate had offered the space at the west end of the building for $1,200 per year, equipment was needed, and although Dr. Spencer had been paid through the first quarter-year, the clinic was living hand-to-mouth and none were sure they would be able to pay him for the next quarter.

Several residents stepped in to carry the clinic, most notably H. Rodney Sharp, who literally floated the facility for the first several years. He contributed substantially to the clinic’s cash flow, but also of his time. As letters show, he served as confidant to Crowninshield, offering advice on matters of business and clinic policy, and hosted gatherings at his “Winter Palace” (better known today as the Sharp Estate) to raise funds for the clinic. Nell Kuhl, former Secretary to Mrs. Crowninshield and a Clinic Director for nearly ten years, remembers that the two were very close.

Hugh Rodney Sharp Sr. was another founding member of the clinic. His financial help and other commitments to the institution helped keep it going in the early years. Photo courtesy of Bayard Sharp

“They were like brother and sister,” she said. She also remembers that Crowninshield depended upon Sharp enormously in those early years, to stand by her side and step in when the going got tough.

“She’d tell him that it was time for him to host a party and he’d do it,” said Nell.

Others remember how popular those “garden parties” were among the winter residents. He was a very creative man, according to friend Mary McLean, and spent a good deal of time and energy beautifying his estate with exotic plants and flowers. His love of European aesthetic was well know and regarded.

He and other members of the community who organized rummage sales and gave whatever they could afford made possible the move to the Fugate building in October, 1949.

Somewhere between the railroad depot and the Fugate building, however, relations between the community and one Dr. Spencer began to decline. Letters from Boca Grande to Marblehead, Massachusetts, Crowninshield’s summer residence, were frequent and panicked. It was the opinion of Jefferson Gaines and Wiley Crews that the doctor was not being accepted by the community, and criticized for his relaxed handling of medical procedure.

Wiley Crews wrote to Crowninshield on July 17, 1949, “If one has no liking or confidence in their doctor no patient can be cured. I have always done everything I could to make the clinic a success, and I fully realize the need for services, but I believe that without the proper physician who can conduct himself to get the confidence of the people generally, all our efforts will be wasted.”

A quick response by Crowninshield suggests that she was aware of the problem and had attempted to resolve it before she left for the summer.

“I spoke with him [Dr. Spencer],” she wrote, “very frankly before I left and said that his job was to make himself liked, that he had offended several people and must be less blunt.”

Crowninshield was very distraught over the tone of Crews’ letter, for more reasons than one. He and Gaines had both written her previously of a bill in the State legislature to build a bridge from the island to the mainland, and the travesty of such a concept struck in her a deep chord of discontent.

“We are very much upset by hearing in two letters that the bill has gone through for a bridge unto the island,” she wrote. “This will absolutely destroy the character of the place, its charm and the desire anyone will have to come to Boca Grande, except tin-canners. You only have to look at the Florida Keys and see how they have been entirely ruined to visualize the type of place Boca Grande will turn into. I hope it is only another of the silly rumors.”

Prior to the building of a bridge to the mainland, the Boca Grande Ferry was a popular, albeit expensive, mode of transport for island residents. Here, the “Saugerties” makes her way to Boca Grande. Photo courtesy of the Fugate Family

Crowninshield returned to the island that winter to a bridgeless island, a new clinic building, and the task of letting its first full-time doctor go. On February 2, 1950, it was decided unanimously by the board that the doctor should resign “due to his continuous ill-health.” His “medical condition” was never specified, and a letter from Dr. Spencer some time later implies that no condition, other than one of conflict” existed.

He wrote on April 3, 1950 to Mrs. Crowninshield, “I am sorry that I was unable to meet the needs of the community and I am sorry that you, yourself, have been placed in such an uncomfortable position. I believe, however, that it was not altogether my fault. Because of a rather demanding attitude on the part of not a few of the local people, any physician who practices in Boca Grande must have the freedom to exercise adequate control over circumstances and his practice…. I am really rather glad to be relieved of the responsibility of conducting the clinic. It is my opinion that, under the present circumstances, the medical problem in Boca Grande is an unsolvable one. There are too many diverse and conflicting interests to be dealt with. Maybe in time all will be as it should be.”

The search for a new year-round doctor began, and Board members were cautioned by Crowninshield that they must be very careful to glean as many references as possible. In a letter to Jefferson Gaines in late April Crowninshield wrote, “If we could only get a good doctor, Boca Grande would be the Garden of Eden.”

It would be some time before all was, as Dr. Spencer wrote, as it should be, but for the time being the clinic was delighted to welcome a Dr. Murphy from Venice, Florida to Boca Grande. On May 23rd he took on the role of temporary doctor, to visit several days a week during the summer months. Due to a successful practice in Venice, he could not commit on a year-round basis, but he was well accepted in the community and the clinic carried on.

Finances had again taken priority that summer as several island residents had fallen on hard times and ill health and were in need of advanced medical attention. One of the residents would require a very expensive operation, a doctor for which could only be found at a hospital in the north, and it was the practice of the clinic in those days to help fund such operations for those who could not afford it.

Meanwhile, while Crowninshield was busying herself with the affairs of the clinic long distance, the modern world continued to creep in on her “Garden of Eden”, and the battle in Boca Grande over the building of a bridge to the mainland raged on.

Gaines wrote to her on May 17the, “The only information I have been able to get about the bridge is just talk and plenty of it.”

Gaines went on to tell her of the talk he has heard and asked that Crowninshield “not quote any of the above since, due to my official position, I cannot express myself. That is why I have taken no part in the fight which is hot here now. I will keep you advised, however, on what we hear.”

The news was received by Crowninshield at a difficult time. That letter was followed with a letter on May 24, 1950 from Gaines expressing his condolences for the death Frank B. Crowninshield.

There was little correspondence that summer as Crowninshield mourned the death of her husband and Boca Grande put on hold its plans of finding a year-round doctor, making do with the weekly visits from Dr. Murphy.

But come October the Inn was anxious to know what the clinic planned to do, and had begun coordinating an alternative plan in the event the clinic would not come through with a full-time doctor that season.

The Doctors from Duke

In fact, by late October, Inn Manager Emory Dunn was successful in hiring a D. James Ingram for the season and wrote to Crowninshield of Ingram’s credentials on October 26.

“I have been successful in hiring Dr. Ingram who is a good friend of Dr. Carlton’s whom you undoubtedly will remember, and who was with us four years ago,” he wrote. “In fact, Dr. Carlton was one of the most popular doctors we have had and he assures me that Dr. Ingram’s ability, manner and character cannot be surpassed. The doctor, his wife, and one child will live with me from the middle of December until the first of April, when he returns to Duke University where he is a professor.”

Crowninshield wrote back that she would be delighted if Dr. Ingram would make use of the clinic facility during his stay, provided he was willing to treat other patients as well. So began a relationship between the clinic, Dr. Ingram, and Duke University that would span the decades to come.

Dr. Ingram took over clinic operations on December 19, 1950 and enjoyed an immediate popularity among islanders. From the minutes of a January Board meeting it is established that the hope was that he would continue with the clinic on a permanent basis. Although his pursuits would lead him elsewhere in the future, his relationship with the clinic lasted his lifetime, and the clinic flourished under his direction throughout the coming season.

Upon his leaving in April, Dr. Murphy resumed his weekly visits to the clinic, and the Board began turning its attention to peripheral tasks, such as the procurement of an ambulance.

It is apparent from clinic letters that the present situation regarding the transport of patients off the island in the case of emergency, was insufficient, and had perhaps resulted in an unnecessary misfortune.

On April 3, 1951, Board member Louise A. Shaw, who was appointed to head up the fund raising arm of the clinic, wrote to island residents, “Recent events have again emphasized in no uncertain way the great risks involved in living on an island with inadequate facilities of ingress and egress in case of emergency, and the only situation appears to be for the clinic to own its own ambulance, in conjunction with a flat car which the Seaboard Railroad will provide to get to the mainland with no loss of time.” “As you know,” she added, “it takes hours to get an ambulance to Placida, if available from Tampa or Fort Myers, and this loss of time could be the difference between life and death.”

The Boca Grande Health Clinic occupied a space on the west side of the Fugate building from 1949 until 1963, paying Jerome Fugate $1,200 in rent each year. Photo courtesy of the Fugate Family.

Contributions began pouring in for the purchase of the ambulance, while Board Directors debated the necessity of the purchase and investigated the cost and feasibility of such a venture.

The task of cost investigation fell on Henry F. Du Pont, and through his ties with Chevrolet, found that the cost of a Sedan Delivery conversion ambulance, the industry standard at that time, would cost upwards of $4,100.

It was his feeling that the clinic did not need the ambulance, and suggested instead a more practical solution, as he writes on April 16, 1951. “Would it not be a more practical idea to approach one of the people in Boca Grande who owns a car which will carry a stretcher, pay them a nominal sum so that it would be at your beck and call when needed, and when they do go on a trip to some hospital, give them adequate compensation?”

His suggestion apparently wins out in consideration of expense, coupled with. the fact that Seaboard Railroad was not anxious to build a flat bed car equipped to handle a vehicle of that size evidently concerned about questions of liability.

Jefferson Gaines was one of the strongest of Boca Grande’s community leaders, serving as president of the Kiwanis Club, Postmaster, and Vice President of the Clinic Board. He also ran the local service station in town. Above: Jefferson and his wife, Clara in 1916. Photo courtesy of Jeff Gaines Jr.

In May, 1951, the Clinic Board mourned the death of one its founders and strongest leaders, Jefferson Gaines, who, despite his efforts toward bringing quality medical services to Boca Grande, did not benefit from them. He suffered a heart attack in the evening and for whatever reason, could not be moved off the island until the following morning. It was late spring and both the Inn doctor and Dr. Ingram had left for the season. Dr. Murphy was only visiting on a weekly basis, and there was no one to tend to his condition. He lived throughout the night but died the following day en route to a hospital in Punta Gorda. His unnecessary death served to reinforce the medical predicament of Boca Grande at that time, for he was one of a sure many who might have lived if conditions had been more favorable.

Although the pressure was still great to find a year-round doctor, the Board could find no one suitable for the position. Despite their trouble, it was imperative at that time to find someone to at least come to Boca Grande for the season, whereby the Inn would be relinquished of responsibility for finding a doctor and the clinic would retain its independent standing. To accomplish this task, the Board called upon its new friend and ally James Ingram, who had by that time resumed his professorial duties with Duke University. Familiar with the requirements of this island community, and having successfully administered successfully to such requirements himself, Dr. Ingram wrote to Wiley Crews on June 28, 1951, to recommend the services of a Dr. Jack Emlet.

“Dr. and Mrs. Emlet are both very competent, professional people and one of the most attractive couples I have ever seen,” he wrote. “I am certain that they will be popular with all of the various groups in Boca Grande. I recommend them highly without any reservations whatsoever.”

The Emlets did come to Boca Grande the following season and were so well accepted that the clinic began an ongoing relationship with Duke University and its medical school for the procurement of doctors who were in training at the school to come to Boca Grande on a seasonal basis. As long as the clinic could not find a year-round doctor, the Board felt it could at least depend upon quality physicians for the seasonal months. And the situation benefited the visiting doctor as well, for the experience gleaned from operating his own, albeit temporary, practice.

A letter from the Director of the medical school, Dr. Hart, was sent to Mrs. Crowninshield in May of 1952 establishing the conditions of the relationship.

“If you so desire,” he wrote, “I will be glad to try to select from my staff men most suited for such a position, and try to arrange to cover the work here so they can take as much as two months’ time off for vacation. That of course would necessitate two men going down each year but it might be possible to have the men go more than one year since they are in training for around six years.”

Island-born resident Wiley Crews was a founding member of the health clinic. His duties were many, but he is best known as the clinic’s manager of the San Marco Theatre. Photo courtesy of Vera Crews Cannon

Duke University was well pleased with the situation, as is referenced in a letter from Dr. Hart in July of 1953.

“It is a pleasure for us to try to work out the best arrangements we can,” he wrote, “toward not only giving Boca Grande a high caliber medical man, but to give men who are going through long years of training on greatly reduced financial incomes a change of vacation under such conditions as Boca Grande offers.”

Certain members of the clinic, however, still held hopes of installing a doctor full time, as Wiley Crews makes clear in a July letter to Mrs. Crowninshield.

“I feel that if the clinic is not successful in securing a full time physician for Boca Grande then it has not fulfilled its purpose and all our efforts will have been in vain,” he writes. “No one knows better than I do what a miserable place this is without a doctor and the time is getting short…”

Mrs. Crowninshield writes back, “I think it would be wonderful if we could get a real good doctor but do be very particular. There are so many incompetent shysters, as we have discovered in the past, and if we do not get a person of the first caliber the people at the Inn will not accept him and then there will be the two doctor situation which the island is not able to support.”

She goes on to explain that Duke University has assured her of six months worth of doctors coverage, and that she has included a codicil in her will appropriating money for the payment of subsidies to the doctors serving in the not-so-busy months.

In the years to follow the clinic would not find a permanent doctor, but it would enjoy the seasonal visits of such popular residents Wilmer “Bill” Coggins and his wife, Deborah, who was also a doctor; Dr. Lyons; Dr. Longino; Dr. Williams and a Dr. Elmer Schmierer procured through the aid of Dr. Ingram.

The status quo was maintained, and the clinic carried on with minor improvements. The theatre was as popular as ever under the management of new Board Director Frank Oliver, the handful of contributors to the clinic had grown substantially, and through contributions of stock from some residents came the establishing of a clinic endowment fund.

It was March 20, 1957 when an application from a young doctor schooled at the University of Maryland and currently interning in St. Petersburg was received by the Clinic Board and accepted unanimously. Dr. George Fritz arrived in Boca Grande with his wife, Ann, on July 8, 1957. With his arrival and under his direction, the clinic would flourish for the next decade.

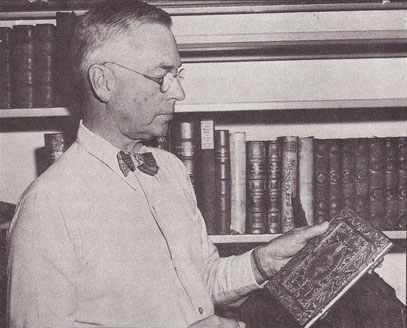

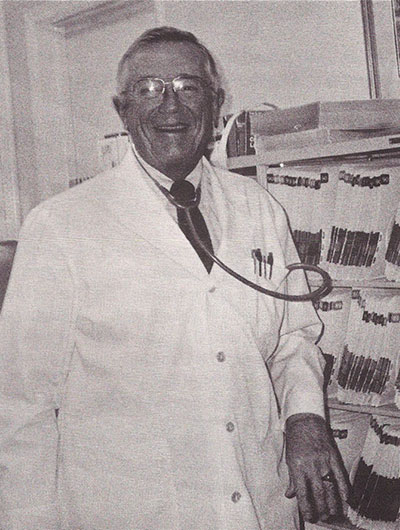

After many failed attempts to find a suitable year-round doctor, the clinic had found such a doctor in Fritz, who stayed with the clinic for 14 years. Photo reproduced with permission from the Ft. Myers News Press – October, 1963.

There is little record of his early days with the clinic on 4th Street, save for references made in local newspapers to the doctor and his wife sleeping in the clinic facility when patients needed overnight care. But it is evident from stories told by former patients that he won the respect and admiration of the community from the start.

“He was one of the best doctors,” says Nell Kuhl. “He was meticulous.”

Nell and others remember that, although he was always available to patients, he enjoyed boating and was, in whatever spare time allowed, out in his boat.

“What Dr. Fritz liked to do was to fish,” jokes long-time assistant Penny Hanson. “He’d drop anything to go fishing.”

According to most, however, what “time out” fishing allowed him to do, more than to catch tarpon, was to study his medical books and keep abreast of the latest breakthroughs in medical technology.

“He could diagnose almost anything,” remembers Nell. “He liked to go there in the boat and study.”

Long-time resident Mary McLean agrees.

“He’d be out fishing and he’d be listening to Johns Hopkins tapes, learning things,” she said.

When McLean’s brother, Jimmy, was suffering from leukemia, and no one in the family knew what to expect from the disease, McLean consulted Dr. Fritz, who told her that he was not expert in the field but had heard from one of his tapes from Johns Hopkins that when living with leukemia, complete paralysis was known to precede death in those afflicted. At that time McLean and her family were relieved to have some expectation of what the disease would bring, as no other doctor had taken them through the process.

“Gerry was the only one who would tell me what was really gonna happen,” said McLean.

Fritz served not only as clinic doctor, but as the island’s quarantine doctor, whereby he was required to meet the foreign ships at the south end of the island and ensure that the men aboard were healthy enough to come ashore. Penny Hanson remembers that the job was often times trying, but always interesting.

“He’d go down to the boats when they came in,” she said, “and come back with a string of ‘em [sailors] behind him. He’d have to give the okay for them to even come to the clinic. They came from every place. Some of them couldn’t even speak English.”

Dr. Fritz would be the first full-time doctor to make a practice in Boca Grande a long-term profession, and his presence helped the clinic win the confidence of the community.

The End of an Era

But it was in the early days of Fritz’s tenure that the clinic was dealt a major blow. After a prolonged illness which she knew she would not recover from, Mrs. Crowninshield passed away in December of 1958.

The last Board meeting she would attend took place on March 31, 1958, as the first of the meetings did, at her late husband’s studio on Gilchrist Ave. From stories told today, folks remember the last time they saw Mrs. Crowninshield as vividly as if it were yesterday.

By all accounts, she knew she would not be returning to Boca Grande when she left in April, and as it was custom for islanders to turn out at the depot to bid farewell to those departing, she boarded the train at the south end so as to make less of a painful goodbye. When the train pulled into the depot, however, she cheerfully emerged at the back of the train to say goodbye to her friends.

As Frank Oliver recalls the day in a July issue of “The Out Islander,” “There were at least a hundred of us gathered at the station to bid her farewell that afternoon. She went north in a private car and boarded it at South Dock. When the train pulled into the station she came out to the back platform and talked and joked with many of her old friends. Everyone was sad at heart by she was the gay cheerful woman we had all known. As the train pulled out to a chorus of sad goodbyes she waved and went into the car, her last sight of the island she had loved for about half a century.”

With her death the community lost a dear friend and the clinic its driving force. It also lost one of its long-time Board members Hugh Rodney Sharp who resigned shortly after Crowninshield’s death. An emergency meeting was called, where upon board members attempted to find ways and means of keeping the clinic in operation. The clinic was in dire straits financially, and it was necessary to launch a major island-wide fundraiser informing young and old, rich and poor, of the clinic’s need. At the same meeting it was the suggestion of Frank Oliver that a tribute be made and send to Crowninshield’s brother Henry F. DuPont.

Under President Frank Oliver the clinic would establish a solid and permanent foundation, and most importantly, its own home. Photo courtesy of John Heffernan

It read, “By her death the board lost its most valuable member and the community a warm and loving friend whose like we may never see again. She was responsible for the establishment of this clinic and worked harder and longer than anyone else to maintain it, even when she was very ill and in great pain as last winter. Many things in Boca Grande were close to her heart, but perhaps none closer than the clinic and its purpose of seeking to safeguard the health of all who live here and visit here.”

Shortly following that meeting Frank Oliver was appointed to carry out Crowninshield’s duties as Clinic President. It was Oliver who not only would guide the clinic through its current financial predicament, but through a very colorful, fruitful era of achievement whereby the clinic established a solid and permanent foundation.

A partially-retired journalist, Oliver first came to Boca Grande in 1946. According to old friend and Reuter’s colleague John Heffernan, Oliver flew down and landed on the Gasparilla Inn’s golf course as was custom in those days. He established residence here in 1953 and although he continued to freelance for the New Zealand Press Association on matters relating to China (on which he was an expert), he rooted himself in the community through his establishment of the Gasparilla Gazette and other pursuits. He joined the clinic Board in 1956 and took over the task of managing the San Marco. He and Deo Weymouth, then Clinic Board member and well known figure to movie going audiences, were responsible for the entertainment side of clinic duties, which seemed to suit their colorful natures.

Oliver proved as President, however, that he had a flair for much more than the “dramatic”.

He was, as remembered by Secretary Nell Kuhl, a man who got things done. “He was the kind of person you could depend on,” says Kuhl, “He would get people going – he meant what he said.”

By April 7, 1961 the clinic was out of financial trouble. Donations of every size from $10 to $1,000 had poured in from the community. Even the poorest gave what they could to keep the clinic alive. As a result the Board relaxed its efforts to maintain the clinic and refocused on improving it.

In May the clinic received a 1952 Buick ambulance complete with stretcher, oxygen and equipment from the Edward R. Ponger funeral home in Punta Gorda, and a fleet of volunteers was organized to man the vehicle in times of emergency. Among those who rose to the challenge were residents Cecil Dooley, Lowell Bell, Eugene Bowe, Darrell Polk, Tommie Cost, Joe Freeman, Alfred Evans, Francis Knight, Rev. M. McGehee, Jack Silcox and Anne Fritz. They would be available on call, as would the three key-holders, Fritz, the Fire Chief and Jerome Fugate, to drive patients in need off island and to the nearest hospital.

The Board began discussing plans to relocate and expand clinic operations. Among the options discussed for relocation was the Theatre building, which was deemed cost prohibitive and soon discarded, and the purchase of the premises they were currently occupying. Another option raised in May of 1962 was the purchase of a piece of land on the corner of 3rd and Park Avenue on which they could possibly build a new facility. The 100 x 150 lot was available through Sunset Realty for $7,500 and although the idea seemed like pie in the sky to some people, Frank Oliver was quite confident that it could be done.

He wrote to Nell Kuhl on May 1, 1962, “We can’t start a campaign for funds without owning a piece of land on which to put a building. I think at $7,500 this piece of land, 100 x 150 is a pretty good buy and that even if the clinic is never build there we can’t go far wrong in owning the land and holding it. We would always get our money back.”

He writes again, this time to Wiley Crews, on July 2, 1962, “It [Fugate building] may have some advantages, but I think these are outweighed by the disadvantages. It is true I suppose that we could add on to the present premises at the back but that wouldn’t mean the interior could be any more convenient than it is now. It horrified me to find last winter that accident cases, blood- covered, etc…had to be taken through the waiting room where patients were waiting. Now is our chance to collect funds and get a new building that will last for years, be designed to fit our needs now and for some years to come and built on land that is now reasonably priced. This is our year of opportunity and I think we’d be foolish to let it go by without doing anything about it.”

With ambitious plans of raising $60,000 from the community, the clinic Board set its sights on a new and improved clinic facility

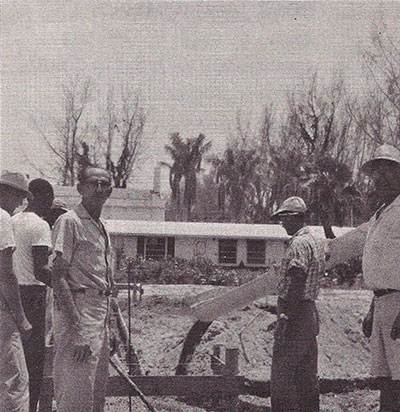

The purchase received the full endorsement of the Board and members set about paving the way to the new and improved clinic. With the close of the sale on September 5, 1962, a building fund was established at Lee County Bank. It was the hope of Oliver that enough funds could be raised to complete the new building by April of 1963. The clinic retained the services of Theo Hargis and Velpeau Kuhl of Griffin Builders Supply for the building of the new clinic, and Board member and architect Edgar “Pilly” Hill drew up the plans. A fundraising goal of $60,000 was set, and by June, 1963 it was reached.

At left: Theo Hargis, Velpeau Kuhl and Huntington “Hunt” Howell break ground for the new Boca Grande Health Clinic.

Although many in the community were enthusiastic about the new building, which promised to be the envy of the medical profession, some felt that the plan was too grandiose, and that the island didn’t need a clinic of such size and splendor. But when the building was finally finished in March, 1964, those who once sneered were whistling a different tune. Oliver commented on this phenomena in a July 5, 1965 letter to friend and fellow board member Huntington “Hunt” Howell.

“It is quite funny,” he wrote. “People who last winter said they were against it are now so proud of it.”

As reported at a February 7, 1966 Board meeting, the clinic came though its first big emergency with flying colors when a ship berthed at South Dock exploded, badly burning several seamen. Two doctors visiting the island came to the clinic to help Doctor Fritz and his wife. One of these doctors, who according to Oliver was a noted surgeon, remarked that he was amazed at the type and scope of medical service available to the island.

Construction of the clinic was completed by March of 1964, and it’s modern appeal and equipment was the envy of the medical community. Those who had first felt the clinic too large and luxurious for an island of this size came to feel differently upon its completion.

The clinic had done well that year, and had finished in the black. A new and improved ambulance had been purchased with help from Oliver’s good friend Arthur Houghton, and Oliver felt as if he had done as much as he could do as President. He wrote to past Board member Cornelius “Toc” Felton on February 18, “Constant illness for both of us [he and his wife, Mary] has caused us to lose so much ground this winter that the results are frightening. I can’t make up for lost time but I can, by giving work all I have, stop the rot and make things a little better – I hope. Last year was ghastly for us and this year is going to be worse.” He added, “People think there isn’t much to being on the board but there is more than they think and anyhow, what I would like is to have the responsibility lifted.”

He offered his official resignation to Secretary Nell Kuhl on November 24, 1966.

She asked, on behalf of the Board, that he accept a position as the clinic’s first ever Honorary Trustee, and he wrote back – obviously touched – that he would do so with pleasure.

“Please be assured,” he wrote, ”that I am available at all times to help in any way I can with the affairs of the clinic, the one project which has given me more pleasure and more satisfaction than anything I have ever been connected with. I pass it a dozen times a day and it gives me pleasure and a lift every time I do.”

Shortly thereafter, the clinic lost its long-time Fundraising Chairman and good friend when Florence Louise Shaw “Auntie Flo” passed away. In February, 1967, Oliver writes to new Clinic President Cornelius “Toc” Felton, of his grief over the loss. His letter is perhaps the finest tribute to her many years of dedicated service to the clinic.

Florence Louise Shaw pledged to serve on the clinic’s board of directors until the day she died, and so she did. “Auntie Flo”, as she was called by her friends, helped the clinic recover from one of its most difficult times, and in honor of her dedication the Board named its new nurse’s residence the Florence Shaw Memorial Home. Photo courtesy of William Morton

“My Dearest Toc, I write to you as an ex-president about our late and beloved Florence who served so long and so well on the clinic board. I remember so vividly the winter of 58-59 when after Mrs. Crowninshield’s death the clinic was in sore straits and in the red. The whole future of the clinic seemed at stake and to Florence fell the task of collecting enough funds to keep it going.

She did magnificently that year and did the same thing year after year until now. I remember with even more feeling what a rock she was…she was a tower of strength. I remember her saying only a few weeks ago that she had no intention of leaving the Board until she died and that is exactly what she did.”

The clinic had again been touched by loss, and a new group of dedicated individuals would join the Board to pick up where others left off. Jerome Fugate and Wiley Crews had stepped down from the Board in recent years, and members such as Deo Weymouth, Hunt Howell, Nell Kuhl, Edgar Hill, William Presley, Kingsmore “Bumps” Johnson and Pershing Thompson would maintain consistency and help keep the clinic moving in the direction set forth by Crowninshield and Oliver.

Deo Weymouth continued to look after the San Marco Theatre, selling box seats and tickets to sold out audiences for movies such as Breakfast at Tiffany’s; Robin and the Seven Hoods with Frank Sinatra; Old Yeller; Help with the Beatles; Americanization of Emily with Julie Andrews; and Sons of Katie Elder with John Wayne. She also took up the task of fundraising, and began hosting what would become an annual party at her place for volunteer ambulance drivers, their families and clinic Board members.

Dr. Fritz was becoming busier and busier and remarked at a 1968 Board meeting that the island was “growing a bit to fast for one doctor to handle.”

The Board did not respond to his request for another doctor, but stepped up its efforts toward finding a full time nurse willing to stay on the island year-round. To make the position more attractive to a resident nurse, members decided to purchase a house for her in honor of their departed friend Florence Louise Shaw. In October of that year they purchased the Johnnie and Honor Downing house for $12,000 and named the house “The Florence Shaw Memorial Home” – still in use by the resident nurse today.

As the sixties came to a close the clinic’s course was well set and the Board’s most vital role became that of adapting to the changes taking place in the world around it. The country was entering the age of liability, and as a result, increased governmental regulation was changing the way people did business. Several visits to the San Marco from a Miami building inspector demanded that the clinic make changes to the Little Theatre to keep with new building and fire codes being established by the State legislature. New regulatory laws were being passed faster than the clinic could keep up with them, and the laws didn’t stop with the enforcement of safe buildings. It had become necessary for anyone operating an ambulance to have obtained a certain amount of training in emergency medical procedure, making it more difficult for the clinic to solicit help in that area from community volunteers. Although Dr. Fritz was initially able to train the volunteers himself, thus adapting to the ambulance regulation, adapting to the new building codes was proving costly. The modern world was closing in on Boca Grande, and the next decade would see many changes in the clinic’s operating and fundraising procedures as a result.

But before such changes were implemented, the clinic was forced to deal with the most pressing of its issues, the announced departure of Dr. George Fritz in June of 1970. After serving as resident doctor for over 13 years, Dr. Fritz received word that year that his application had been accepted at Baylor University in Houston, where he hoped to pursue his lifelong dream of becoming a dermatologist. He had been accepted for admission that year but was persuaded to stay on another year to give the Board enough time to find a suitable replacement.

Compounding the loss of its first long-term doctor, the clinic was in upheaval following the recent death of Board member Pilly Hill, the resignation of Toc Felton due to ill health and the resignations of Theo Hargis and Joe Junkin. Its situation was described in the minutes as the “1970 crisis”.

That spring, Hunting Howell took over where his predecessor Toc had left off. He brought on board two new directors, Bayard Sharp and Joe Freeman, to help carry the load. To find a new doctor, he consulted the clinic’s old friend and former M.D. James Ingram, who aided the Board in securing the services of a Dr. Henry out of Venice, Florida.

Dr. Richard Henry arrived in the fall of 1970 and it is implied through the clinic minutes that, although folks were sorry to see Dr. Fritz go, the transition was a smooth one. The time was indeed ripe for change. In fact, a new amendment to the bylaws enacted under Felton dictated that directors be held to term limits, and as a result, directors like Nell Kuhl, who had served in some capacity since the clinic’s inception, stepped down from the clinic board.

Nell was quoted in the minutes as equating her leaving the board after so many years to the sadness of leaving an old friend. She was not the only one leaving her old friend. Deo Weymouth, who had faithfully looked after Little Theatre operations since the early 1950s, was part of that first rotation. Both Deo and Nell would join Frank Oliver as Honorary Members, and eventually Deo would return to manage the Theatre’s affairs, but the island was growing and the clinic was no longer the project of just a few. Its supporters were many, so where it lost a certain continuity with the bylaw changes, it gained through the talents and new ideas of a greater number of island residents.

By 1972 growth on the island had taken a dramatic upward turn and it fell on President G. J. L. Griswold to consider the impact of such growth on the clinic’s future. It was he who brought about discussion on the availability of two vacant lots across 3rd Street north of the clinic (which now serves as the clinic’s parking lot), and subsequently convinced the Board to purchase the lots for future expansion. As did his predecessor Frank Oliver in 1959, Griswold looked ahead to the day when the clinic would no longer be equipped to handle the number of patients in need of service, and he felt strongly that the clinic would eventually need to expand.

He was also the first to propose solutions to problems that had first presented themselves in the sixties, particularly the liability of the Theatre building.

By 1973 business had slowed at the San Marco and the clinic had begun to lose money on several of its showings. For as much as islanders loved their Little Theatre, the modern world was capable of offering them so much more in terms of the movie going experience. The shell floor of the Theatre was charming, but a latecomer shuffling down the aisle could prove disruptive. And although it was the only show in town, a good rain thundering down on the tin roof could keep one from hearing the shows.

Griswold was the first to suggest that if and when the school building (Community Center) was renovated and the auditorium ready for use, the clinic board might consider moving the showing of their movies there where the seats were more comfortable, the acoustics were better, and heating and air conditioning were available.

By next season, however, the movies were doing better, and attention from the financial affairs of the clinic was averted for the time being with the departure of Dr. Richard Henry and the arrival of a Doctor Henry L. Wright of Tampa, FL.

A long time friend and colleague of Ingram’s, Dr. Wright arrived on September 1, 1973.

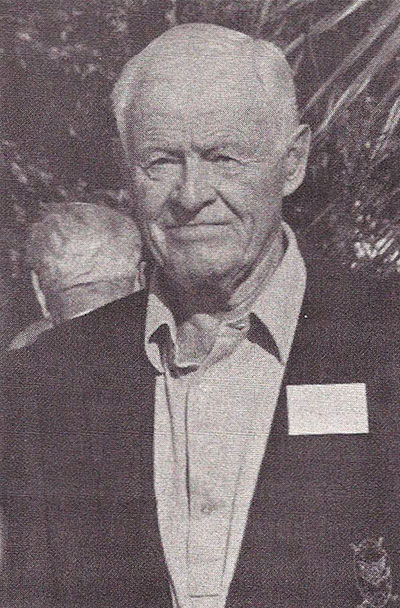

Dr. Henry Livingston Wright first came to the clinic in September, 1973, and although he has since retired from his position as Medical Director, he continues to see patients at the clinic on a part- time basis.

Like Ingram, Wright was an alumnus of Duke University where he studied premed and attended medical school. After serving a residency at Ochsner Foundation Hospital in New Orleans, he had settled down to a twenty-year practice in Tampa, specializing in Obstetrics and Gynecology, where the Boca Grande Health Clinic found him.

In a letter of introduction sent out to members of the community in 1973, Griswold wrote, “He [Wright] is 49 years old, married with two children, knows Boca Grande and enjoys it very much. His references, both professional and personal, are excellent.”

Dr. Wright would go on to surpass the good reputation that preceded him, and to become a permanent, driving force as he remains today – behind the clinic’s future advancement.

Upon his arrival he quickly involved himself with the affairs of the clinic and the community. He took up the task of training the ambulance volunteers, took part in the launching of the very popular Fourth of July fish fry, held at the Gasparilla Inn Beach Club for many years, lobbied for the clinic for special treatment concerning ambulance regulation, and kept the Board abreast of the changes occurring in the medical community.

Meanwhile, the Board continued wrestling with problems posed by the Little Theatre. Deo Weymouth, who at some point had returned to manage the movies, stepped down from her post in 1976, and the clinic’s insurance company announced that same year that it was reluctant to write liability insurance on the movie theatre and would offer only nominal coverage with limits of $10-20,000. It was agreed at that time that the clinic would not self insure in view of the potential exposure, and a motion was made that the clinic no longer assume responsibility for the operation of the movies.

The Board realized what a tremendous loss the theatre would be to the community, and members first attempted to hand over the movie business to another island organization. But as those attempts were fruitless, it decided in 1977 to transfer the operation of the movies to the community center, as was suggested by Griswold in 1972.

The San Marco closed is doors on a rich and colorful past, laying abandoned for many years before it was sold and restored to fulfill another purpose. Although folks were sad to see the Theatre shut down, the old relic had remained in operation longer than one could have expected considering how fast the world was changing outside Boca Grande. Besides, the loss was overshadowed by greater concerns for the continued safety of those who now depended on the clinic.

Reliable ambulance service was the most important issue facing the Board, and regulations pertaining to the ambulance and its drivers had continued to tighten. It was now required under Florida law that one of the two volunteer ambulance attendants must be a qualified “Emergency Medical Technician,” and have completed an extensive 120-hour course in emergency care. The courses were entirely funded by the clinic, but there were few who could make such a commitment of time. Where the clinic once boasted twenty volunteer drivers, it now had only five. Dr. Wright reported to the Board in 1978 that with the future population growth the need for independent ambulance service would most certainly be needed.

It would be some years before the discussion of such a plan would officially take form, and until that time folks in Boca Grande did what they have always done best. They made do.

In the meantime, the clinic maintained a steady course through the early 1980s. Those years saw the arrival of lifetime resident Janice Busby to the clinic staff, the clinic’s discontinuance of movie sponsorship at the Community Center due to the breakdown of its 1948 movie projector, the purchase of another plot of land across from the clinic on 3rd Street, and the first real discussion pertaining to the need for an expanded clinic facility.

Population is Growing Fast

As predicted by past Board Members, the demand for medical services due to a growing population was beginning to exceed the clinic’s capacity. In March of 1985 the Board decided it was time to seek the services of a second doctor and to look into the possibility of enlarging the clinic to meet the needs of a second physician.

The growing population also served to point out the inadequacy of the island’s ambulance situation, and the Board had begun to apply pressure on the Lee County Commissioners to provide the island with an Advanced Life support ambulance – a service which would not just transport a patient to the nearest emergency room, but work to stabilize patients en route. Such services were available just about everywhere else, and with the amount of money islanders were contributing to the county via tax dollars, they felt they deserved as much as their mainland counterparts. Volunteer EMT drivers even resigned from service for a time to attempt to force the issue with the commissioners.

Finally, by 1988 an agreement was reached between Charlotte and Lee County whereby Charlotte County EMT would offer service to Boca Grande from a station in Grove City (shared with the Englewood Area Fire Control District) and Lee County citizens would fit the majority of the bill through specially assessed taxes. Although the situation was not in the best interest of islanders and response time was extremely slow, a union between the two counties seemed the best way to address Boca Grande’s problem. Islanders were assuaged for the time being with talk of another station being established in Placida, financially backed by Lee County and staffed by Charlotte.

While forced to “make do” with the ambulance service the two counties were prepared to offer at that time, the clinic Board, by 1989, had taken matters into its own hands where the expansion of the clinic was concerned. At its March meeting the Board unveiled to the community ambitious plans to expand the clinic facility, and announced that its capital fund drive, thanks to the efforts of Fundraising co-chairs Mary Sharp and Patty Hobbs, had already raised $654,000 towards its $1 million goal.

Board President Admiral Chester Nimitz, the driving force behind the clinic expansion, reported at that time that the Board intended to enlarge the clinic to handle two doctor/nurse teams instead of the one team presently there; to purchase more sophisticated accounting and computer equipment; and to offer a furnished residence for the replacement of Dr. Hank Wright, who had recently announced plans to retire in 1991.

Board President Admiral Chester Nimitz spearheaded the plan to build a new clinic that could administer to the growing population.

For some time Dr. Wright had served as the only doctor in a community whose growth proved very demanding. His plan of retirement, according to one report given by Bayard Sharp at a fundraising event, is what pushed the Board in the direction of expansion.

Sharp qualified the Board’s reasons for expansion to a crowd gathered in the Pelican Room of the Gasparilla Inn. He was quoted in a local newspaper as saying, “This campaign started because our popular Dr. Henry Wright made noise about retiring,” he said. “Lord knows he deserves it. With the island growing we don’t need another doctor. We need two doctors.

With a healthy sum of money in pocket and every early indication of reaching their goal, clinic officials brought their plan to the Lee County Commissioners, where they were abruptly – in the height of the Board’s optimism – turned down. County regulations stipulated that the cost of adding onto property could not exceed half the book value of the property, which would have limited the board to spending no more than $20,000 for the expansion. It was also noted that since the present clinic building stood four feet too low, it could not receive flood insurance.

The news did not deter the Board, however. Members voted unanimously, and in a matter of days, to build a new clinic instead. Thanks to the vision of several past clinic directors, such a quick move was possible and the Board began making grand plans for the clinic’s three lots on 3rd Street.

When plans for the new building were announced and it became evident that the clinic would need more than the $1 million initially anticipated, islanders stepped up to help in any way that they could. Seven major contributors of $100,000, Bayard Sharp, Arthur Houghton, Steven Schwartz, Jane Engelhard, Hugh Sharp, George Weymouth and Richard Diebold, helped pay the way for the project, and contributions from the community to the tune of $900,000 were received in a matter of two months. Whatever folks could give, they gave – some in the form of labor. Harold Bowe, for instance, was commended by the Board at the time for volunteering to clear the land – a task that would have cost the clinic upwards of $10,000.

Medical Director Hank Wright and Architect George Palermo began working on plans for the building in April, 1989, with their sights set on designing a Spanish-style building similar in design to the Community Center. A completion deadline was set for the summer of 1990.

Although the Board’s ambitious plans allowed little time for other pursuits, spring brought a rash of fresh debate over the location site of the proposed new ambulance station planned to serve Boca Grande and Charlotte County residents, and the clinic took its part.

The station was to be built at the corner of Placida Road and Cape Haze Drive and paid for by Lee County to service its residents in Boca Grande. Charlotte County agreed to staff and maintain the station. All seemed to be going as planned until Charlotte County Commission Chairman Bill Burdick proposed that the Charlotte portion of Gasparilla Island might prove a better site for the station, considering the commitment being made on the part of Lee County and the problems facing the island community in terms of the response time of off- island EMS service.

Dr. Wright led the charge for the new proposition. He was quoted in a local newspaper as saying that while the paramedics that currently served Gasparilla Island were great once they arrived, they often times took over half an hour to get to the island. He felt if the station were located on the island, and there was any problem getting off the island, the clinic would have paramedics on-site who can stabilize people.

“We’re not equipped to handle heavy trauma,” he said.

Most of the mainland residents were displeased with the proposition, and waged a considerable campaign against it. Lee County was equally displeased with the perceived lack of cooperation on the part of Charlotte County, considering the commitment of funds it was bringing to the project. At one point Lee even threatened to take its dollars elsewhere.

But the mainland won the war, with Lee County promising to review the response times of the new EMS service to the island and revaluate its decision at a later date.

According to Janice Busby, the response times were consistently unacceptable, and the clinic persisted in its efforts to push Lee County into action.

Meanwhile, the Board had secured the services of Doctor Arthur Moseley, a physician retired to Boca Grande and willing to serve on a part-time basis beginning in July. It had accepted the final plans drawn up by Palermo and a bid for construction of the new clinic from Gulf Constructors International, Inc. out of Sarasota, the same firm responsible for the building of the Engelhard and Sharp estates, and the Asolo Performing Arts Center in Sarasota.

The building of a new and improved Boca Grande Health Clinic began in January of 1990, with hopes for completion by summer.

Ground breaking began in January of 1990, and although there were some who felt that the new clinic was a tad too grandiose for a little island, the community took pride in each step of its completion. Still fresh in the minds of- some, after all, were the same words spoken in relation to the current facility.

While on the glide path to a successfully launched and executed project, the Board came to consider once again, the unacceptable ambulance situation we still faced. Steven Schwartz had offered the clinic a space up at the north end to house an EMS station, and while that plan was being considered, it was while deciding what to do with the current facility that a better solution presented itself. Rather than sell the old clinic facility, or turn it into a large day care center as had been suggested, a deal was struck between Lee County and the clinic whereby the clinic would lease the building to the county for $1 a year for twenty years – $20 for 20 years.

The new building was completed and ready for occupancy by December, 1990.

So it was the Boca Grande Health Clinic that came to occupy the building we are all familiar with. In the years that followed the move to the new facility, there would be no major battles to be waged and the Board would turn instead toward the future care and secure financial foundation of the clinic. It would find a well respected and well-liked replacement for Dr. Wright in Dr. Richard Morrison, who after a long and distinguished career specializing in vascular and thoracic surgery in Venice, FL, took his long-time friend and golfing buddy Hank Wright’s advice and decided to give Boca Grande a try.

Clinic directors stand proudly before the new Boca Grande clinic facility on its opening day. From left: Amor Hollingsworth, Mary Morrison, Dr. Dick Morrison, Donna Moore, Steve Seidensticker, John Heffernan, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Greg Magratten, Janice Busby, Dave Sherman, Dr. Dennis Dorsey and Dr. Henry Wright.

Today, as one waits his/her turn in the cozy waiting room of the handsome clinic, there is no sign of the struggle that marked its first 50 years, or of those who worked tirelessly to see that those who lived on this remote barrier island had access to quality medical services, or of those who suffered prior to the establishment of the Boca Grande Health clinic. In fact, the only perceptible difference in the clinic, on first glance, is the comfortable feeling one gets – as if in their own living room – upon entering the building. But upon second glance, one might notice the paintings on the walls, created by Frank Crowninshield in his studio on Gilchrist Ave., or the rug wall hanging weaved with loving care by past clinic President Admiral Chester Nimitz, or the bronze plaque on the door honoring past President Louise Crowninshield. Or perhaps one will notice that the patients called in to meet the doctor are greeted with a familiar smile and greeting, and most times by their first names. One gets the feeling that those who staff the clinic are not only seeing patients, but happy to catch up with old friends.

Therein lays the unique nature of the Boca Grande Health Clinic, an institution born of a group of dedicated and resourceful pioneers, and carried throughout the years by their friends, neighbors, sons and daughters – the community. As island daughter and Clinic Administrator puts it, “The plaque on the wall reads, ‘In honor of the community’ and that’s what this is – because we wouldn’t be here without the community.

Here’s to the next fifty years!

A Letter From Dr. Henry Livingston Wright

I have been asked by Lynne Hendricks to write something for this book about the history of the Boca Grande Health Clinic which is celebrating its fiftieth year on existence this year. Fortunately, she has prepared a factual account of the happenings during the clinic’s life span. What I have to say is anecdotal, and must be taken with a grain of salt, though I have tried to keep it as accurate as possible.